“Since You’ve Already Lost…”

A glance at revulsion, reform, and religious who minister in the age of mass incarceration

By Mike Dorn, OFM Cap.

Nationally, the souls of almost 2.3 million are incarcerated, with 1 in 5 for a drug-related offense. In the face of such a reality, taking concrete steps to address mass incarceration born out of consistent prayer is critical. Archbishop Desmond Tutu embodied such spirit one day well before the end of apartheid during a prayer service at Cape Town’s St. George’s Cathedral. When police entered armed with guns and lined the walls, he responded: “You are powerful. You are very powerful, but you are not gods and I serve a God who cannot be mocked. So, since you’ve already lost, since you’ve already lost, I invite you today to come and join the winning side!”

The prison-industrial complex may be powerful and running at full steam, but it has likewise already lost. As Capuchins, Catholics and other Christians, we must work together to bring others to the winning side of a restorative justice model sooner than later! Here’s a glimpse as to why it matters:

Solitary Watch reported that Todd Ashker was sent back to solitary last year via “ad seg” (administrative segregation), after only 13 months in general population and after serving 28 years in solitary confinement because ‘his life was threatened.’ Ashker (among others), organized a 2013 hunger strike that engaged 30,000 inmates which led to significant changes to Pelican Bay State Prison (where he resides) and elsewhere.

Moreover, The Marshall Project tells the story of Imani, a 16-year-old in Syracuse, NY arrested and charged with robbery after a dollar store clerk accused her and her friends of shoplifting. She was placed into solitary confinement (aka SHU/Security Housing Unit) for 32 days after filing a grievance on one of the officers in the maximum-security adult jail. This happened in 2016, a year after NYC banned the SHU for anyone 21 and younger. It was also a year after the death of Kalief Browder, the nationally-known story of a 16-year-old Bronx teen arrested for allegedly stealing a backpack and later put into solitary confinement for two years on Riker’s Island (three years in detention) before the charges were dismissed. In 2015, he committed suicide due to the effects of his incarceration.

These stories, and the vast majority of their kind which remain untold or rather unheard— are all seemingly deafening alarms that have been sounding for decades but only in the last several years have begun to be heard on a larger scale. Why has it taken so many cell phone videos, research journals/books, films and nationwide protests to educate parts of society largely unaware of this issue about its ongoing reckless fruit?

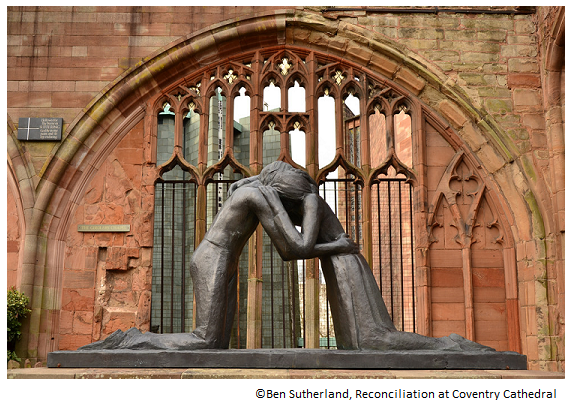

The answers given are as convoluted and elusive as the issues themselves, yet the crux lands somewhere in the realm of denial of our roots. Thus, until we as a nation of indigenous, black, brown, white, documented and undocumented peoples can assemble throughout the country for some form of truth and reconciliation commissions (TRCs) to discuss our troubled histories and the ongoing consequences— systemic justice and peace will remain elusive. As attempted in South Africa and at least 42 other countries; TRCs are not perfect, one-time solutions to decades of racism and injustice, but in the right political environment they are agents for promoting restorative justice and reconciliation-based societies.

As Capuchin Franciscans, our vows and our fraternity bind us to the work of repairing and rebuilding relationships. Although our efforts may appear small, both our physical and spiritual presence- matter. In Milwaukee, Capuchin friar Francis Dombrowski is on call as a Catholic priest to the Secure Detention Facility and the Women’s Correctional Center. When asked about the difficulties of prison ministry, he points out the challenges of contextualizing their backgrounds in light of past trauma, abuse, etc. He adds, “trying to help the person clarify what is important to them and what hurts the most and to motivate them by appealing to their strengths, their faith, their trust in God. We use God's word to give them hope, and we brainstorm for a step out of their situation, one that they feel they can do and want to do.” Additionally, Dombrowski also belongs to a citizen’s group that lobbies senators and assembly members in Madison to reform some of the parole policies and revocation practices so that offenders might have an opportunity for alternatives to incarceration, such as outpatient AODA (Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse) counseling.

Likewise, Capuchin friar Joachim Strupp, who completed four years of prison ministry at the federal level in Lompoc, CA, also speaks from a place of advocacy- “[Inmates] are frustrated of being left in the dark for long periods of time in regard to medical treatment, legal appeals, dates of release, etc. For many, there’s the torture of their inability to help their families with the problems caused by their imprisonment; and many complain of the lack of programs to help them prepare for life outside of prison.” He wants the public to know that “many see their incarceration as an opportunity to turn their life around, but unfortunately our society often doesn’t help them do this once they’re released.” Dombrowski agrees, “Right now there are too many obstacles to rehab.”

Despite the seemingly endless roadblocks of a non-rehabilitative and profit-driven corrections system, it’s safe to say that mass incarceration and it’s business model will eventually unravel because it has been spiritually and morally bankrupt from the moment its architects went to the drawing board. That said, a system that has been so relentless on punishment rather than rehabilitation for over 40 years won’t dissolve overnight. Nationally, it’s at a snail’s pace of progress in the right direction. Still, despite Todd Ashker returning to the SHU, Solitary Watch has reported that “in California’s ten high-security prisons, the number of people in [the SHU] fell dramatically—from 2,876 in September 2015 to 444 in March 2017.”

If both lay, clergy and religious can learn more about the inmates in this losing industry through volunteering as chaplains, assisting in community re-entry programs, or advocating on their behalf politically, perhaps the closer we’ll all get to a winning system of restorative justice and reconciliation.

Photo credits: 1) "Prison crowded", CA Dept. of Corrections, Wikimedia Commons; 2) "Reconciliation at Conventry Cathedral" Flickr, Ben Sutherland, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 license